Brown Brings New Haptics Approaches to Robotics at Hopkins

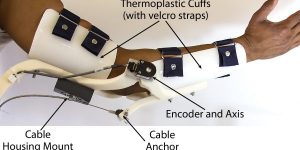

LCSR’s newest faculty member Jeremy D. Brown, assistant professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, came to Johns Hopkins in January from the University of Pennsylvania, where he was a postdoctoral research fellow. Brown investigates novel methods of haptic  feedback for devices such as upper-limb prosthetics and surgical robots. Haptic interfaces like those Brown develops seek to endow amputees with a sense of touch through their prosthesis and improve a surgeon’s accuracy and precision when performing delicate procedures with a surgical robot.

feedback for devices such as upper-limb prosthetics and surgical robots. Haptic interfaces like those Brown develops seek to endow amputees with a sense of touch through their prosthesis and improve a surgeon’s accuracy and precision when performing delicate procedures with a surgical robot.

“Haptics is the science of utilizing our sense of touch as a communication channel. Haptic feedback devices work with our sense of touch to constantly communicate information to us,” Brown said.

Brown’s research focuses on haptic feedback methodologies for human-robot interfaces with a specific emphasis on medical applications. He will teach a new course in the fall related to his research called “Haptic Interface Design for Human-Robot Interaction.”

Brown’s Haptics and Medical Robotics (HAMR) lab seeks to better understand the human perception of touch as it relates to applications of human-robot collaboration. HAMR researchers are particularly interested in medical robotics applications such as minimally invasive surgical robots, upper-limb prosthetic devices, and rehabilitation robots. Lab members build better interfaces between humans and robots, whether they work together to accomplish a task or the robot acts as an extension of the human body.

“The surgical robot acts as an intermediary between the surgeon and the patient. If you were to touch tissue with your surgical tool, you currently cannot feel that, you can only see it. Adding haptic feedback would mean adding a mechanism that allows the surgeon to actually feel the result of palpating the tissue,” Brown said.

Brown recently received an NSF CRII grant for a project which started in August that focuses on developing better haptic interfaces by providing the robotic system with information regarding the physiological changes that occur in the human body when it is mechanically coupled to the robotic system.

Brown recently received an NSF CRII grant for a project which started in August that focuses on developing better haptic interfaces by providing the robotic system with information regarding the physiological changes that occur in the human body when it is mechanically coupled to the robotic system.

Brown was influenced to come to Johns Hopkins by Katherine J. Kuchenbecker, one of the country’s top haptics researchers, who served as his mentor and postdoc advisor at the University of Pennsylvania. Now at the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems in Stuttgart, Germany, Kuchenbecker completed her postdoc at Hopkins under the direction of Allison Okamura, who is also one of the country’s top haptics researchers and someone Brown considers a mentor. Now at Stanford University, Okamura began her career at the LCSR, and she spoke highly of the people and the prestige of the program. Both Kuchenbecker and Okamura’s research labs had many former Hopkins students whom Brown had gotten to know over the years through his PhD and Postdoc.

“People have been whispering Hopkins in my ear for quite some time now. The place built up this reputation even before I’d ever actually visited myself. I just knew this was the place to be,” Brown said.

Brown earned his PhD at the University of Michigan before going to Penn, where he worked on haptic feedback for minimally invasive surgical robots. He says that the skills he developed during his dissertation were extremely relevant to his new work in surgical robotics.

“The devices are totally different, but the approach is very similar in the sense that the human operator has some means of controlling this device, whether it’s a prosthetic hand or surgical device. They have the ability to watch what they’re doing, but currently there’s no haptic feedback. They can’t really feel what they’re doing,” Brown said.

The LCSR’s reputation as a leader in the field of robotics and medical devices is largely responsible for drawing Brown to Hopkins, as were the achievements of stellar LCSR faculty, including Russell Taylor, Gregory Hager, Louis Whitcomb, and Noah Cowan, he said.

“LCSR has built up a very strong research reputation over the past decade, and the chance to be in a place where I am down the hall from and knock on the doors of people whose names I have come to recognize over the years because of their accomplishments in the field of robotics is incredible,” Brown said.

Brown predicts that, 30 years from now, technology will have advanced to the point where interfaces between humans and robots will have become seamless and intuitive.

“To the surgeon, it will feel like the robot is part of their own body or an extension of their body. For an amputee, they will be able to control and feel with their prosthetic limb, the same way that they do with their intact, healthy limb,” Brown said.